The Kurow Cure: worth another crack

We are thrilled to be able to present this article by Professor Don Matheson, with illustrations by the awesome Bob Kerr, as presented to the Fabian Society.

With thanks and acknowledgements to those mention above.

Please enjoy this thoughtful read.

UCAN

An address to the Fabian Society of New Zealand

88 years ago a mass migration of economic refugees was occurring in Kurow, North Otago as desperate families moved into the area in search of work from the Waitaki hydroelectric dam. Some even brought their own spades, in case the government did not have enough for them. In fact there was not enough work and an informal settlement formed of desperately poor, unemployed families, on the banks of the river. The local school roll shot from 30 to 300. Andrew Davidson, the local teacher, Gervan McMillan, the local doctor, and Arnold Nordmeyer, the local minister, came together and built a health and its determinants response to the poverty that they saw. It was called the ‘Kurow Cure’ – a scheme based on the concept of justice rather than charity.

Bob Kerr, our Mt Victoria artist, has created these images of that discussion in his work, The Three Wise Men of Kurow. His work summarizes the key concepts behind the health response they envisaged:

So the concept of a free, universal and comprehensive health service for all New Zealanders was born and incubated in Kurow. It became the blueprint for the Social Security Act of 1938, one of the first internationally recorded expression of what today sits within the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. It is known as Universal Health Coverage, which has been developed by World Health Organisation and the World Bank – with a lot less clarity but the same intent as the Kurow Cure.

So what happened?

In this discussion I will explore what has happened to this vision of health service provision, 80+ years later, especially the last idea, that:

- It should be free, it must be complete and it must meet the needs of all the people

Many aspects of the social security act transformed the health and life chances of generations of New Zealanders, especially free hospital care. However free primary health care for all did not become a reality. This particular provision proved controversial right from the start.

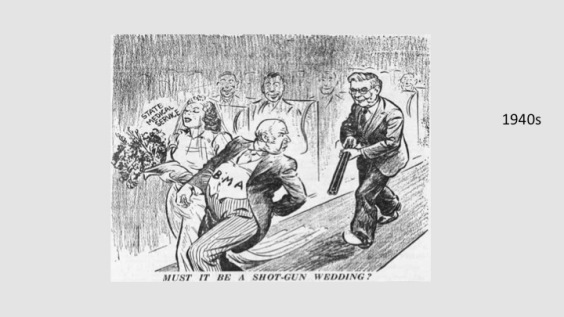

Medical resistance1

For the next 60 years, attempts by governments to introduce free health care were effectively and passionately blocked by the Medical Profession, then called the New Zealand branch of the British Medical Association (BMA). It was seen as an affront to their right to charge their own fees, and the thin end of the wedge of “socialized medicine”.

Many of the members had come to New Zealand to get away from the NHS. It was also strongly argued that the state should not interfere in the special relationship between the doctor and the patient – both the relationship with the doctor’s wallet and, more broadly, on ‘his’ ability to do the right thing for the patient.

80 years later, the protagonists in this conflict appear to be changing sides.

The NZMA with its 2011 statement on health equity, comes close to repeating McMillan’s mantra, backing accessible care and greater attention to the social determinants of health.

The government, on the other hand, as we have seen by the feedback to the draft NZ Health Strategy, had to be cajoled by the health sector and professional groups to give greater emphasis to health equity.

Changes in the health sector

But the sector ain’t what she used to be. From the 1970s onwards this ‘special’ three-way relationship, between the medical professional providing primary health care, the state and the public, began to change. The formation of group practices, the concept of teamwork with nurses, the introduction of contracts, the appearance of professional ‘managers’ within general practice settings, have all pushed the provision of general practice towards a more complex model of care.

Medical influence on the sector has not entirely dissipated, but evolved into new forms. The MBChB2 leadership for now is being replaced by the MBChB/ MBA3, and soon the MBA. On its own. The obstructive industrial position of the BMA around user charges has been absorbed into new medical corporate entities, IPA4s, which have further evolved into PHO5s. Even more ‘disruptive’, is the recent arrival of medical care companies into the sector, such as Nirvana Health group, Green Cross Health and others springing out of PHOs. These are increasingly shaping the sector – and changing its politics with the dilution of medical power – adding multiple partners to this professional – state marriage and the imperative to deliver a return on investment for shareholders.

So although the equity word is used freely within medical professional circles, the control of the primary health sector is shifting to a series of semi corporate, corporate, and international business entities.

Have we made any progress?

So what progress have we made on bringing free care to those who need it 80 years on?

Various attempts by successive governments have been made to improve primary health care access, including the creation of group practices and trials of capitation in the 70s and 80s. Helen Clark’s first attempt to introduce medical contracts in the late 80s was an attempt to control fees charged to patients. But with a change in government, it was not till the 1997 coalition agreement between National and NZ First that free under six care was successfully introduced.

The early 2000s saw the introduction of enrolment and capitation as a system wide contracting instrument for PHC funding, a sector wide discussion on the meaning and drivers of inequity, and a large injection of government funding into the sector. This funding effectively halved the number of people having difficulty accessing care and, at one stage, had NZ leading world rankings in primary care physician satisfaction ratings.

The 2010s have seen free care for under 6s extended to after-hours care and in 2015 zero fees for under 13s were introduced in New Zealand.

Free care is a no brainer. There is ample evidence that out of pocket payments, particularly for poorer and sick people, adversely impact on their health. Since the Rand study of the 1970s, it has been consistently shown that, faced with increased user charges, people use services less, irrespective of the severity of their condition. This is bad for people and bad for the effective use of health services.

How well are these current instruments working?

According to the New Zealand Health Survey, the answer is not very well. Almost one million New Zealanders report difficulty accessing primary health care services, the majority because of the cost barrier, closely followed by service availability.

The number of conditions appearing in hospitals, which could have been more appropriately treated in primary care, is increasing, with persisting higher rates for Maori, Pacific and people on low incomes.

Even capitation, the funding instrument vital to the delivery of a population approach, has not been applied in an equitable fashion. The introduction of near universal capitation has also not lived up to its policy intent, and is now an instrument that could be making health equity worse. Maori are much less likely to be on a capitation register, with some 10% of Māori currently unregistered. The implications of this, in the age of the Medical Home, is that the community with the greatest need are likely to remain, or become, the medically homeless.

Why do inequalities persist?

Some of the reasons that the policy solutions such as PHOs, DHBs and capitation have so far failed to take equity seriously are worth exploring.

Primary health organisations

The policy of the PHO policy intent was to pursue equity, represent community views and aspirations, and lead a coordinated population health approach. But these organisations have rapidly morphed into provider dominated organisations. They have been consolidated to the point that they have, with some exceptions, lost any relationship with discrete populations, and have weak accountability to communities. PHOs have struggled in many cases to be more than a GP funding post box. Although they are now much bigger they have yet to demonstrate being better than smaller PHOs . Many are focused on buying practices and some are busy plotting the overthrow of their DHB with the talk of fund holding and social investment. Moving the sector towards a population equity focus has disappeared as a priority for many PHOs.

District health boards

The situation for district health boards (DBHs) is more complex. Some in the last decade did take their population health responsibilities seriously, began to invest in their communities, with a measureable improvement in health access for the most vulnerable, and the added bonus of reduction in unnecessary hospitalization. Some even went as far as investing in housing. With the financial squeeze of the global financial crisis, the DHBs have become increasingly brain dead, with an obsessive focus on their end of year financial result, disinvesting in community services, and focusing on Minister defined targets that were reset on a very narrow set of activities that belied the complexity of the organizations they were meant to guide.

A recent Treasury report6 shows that over the last five years most DHBs have shifted financial resources meant for primary care and community services into the hospitals, in attempts to make ends meet. At the same time they have shifted some hospital functions into the community. This amounts to a significant shift in financial resources in the opposite direction to their own planned intent, the policy intent of their organizations under the NZ Health and Disability Act. It has contributed to the failure to address equity of access at the community level. It is also a failure of the existing governance and oversight structures that such a high level of shifting costs onto the community has not been called out.

Having said that, the DHBs and their predecessors, the hospitals, have maintained free access for the whole population, and consistently done this since their inception. While the primary health care sector has failed to achieve equity of access, the hospitals have been much more successful in this regard. This includes effectively fighting off a neoliberal rush of blood to the head in the 1990s when the government of the day attempted to introduce user charges.

Of course the economists, managers, funders and planners all think this is mad. Why would we have access barriers to the front gate and least expensive part of the system, then have free rein for the rest, up to the most expensive offering? It does not make, economic, system, or efficiency sense. However from an equity perspective, it is the continuously open doors of our hospitals that have softened the impact of an inequitable primary health care system for generations of New Zealanders.

The way forward

So what are the lessons learned from the time of the Kurow Cure? The strongest structures in the health sector from an equity perspective and low access barriers remain the public hospital system. It has become part of our culture, or our “socialist streak” in the words of the current prime minister. We have failed consistently to introduce a similar public service culture into the primary health care sector. This sector was built on a small professionally led business model, and is fast becoming a large corporate model, with its focus on shareholder value rather than health equity.

Going forward, my belief is that the institutional instruments such as DHBs, PHOs, and capitation could all be effectively used to reduce health inequalities. But the overall intent is lacking.

At the highest level, the concept of the right to health within a national constitution would help maintain this strategic focus. This would help drive the cultural change required to shift the bureaucracies toward a better balance of economic and human values.

Within the health sector, the revised NZ Health Strategy generally has a much weakened focus on health equity, and is intending to take us into new territory with its emphasis on “social investment”.

The hope here is that with the financialisation of services to the poor, the actuaries and the quants with their algorithms from the insurance world will achieve what the doctors, PHOs, DHBs etc have so far failed to do.

On a more positive note, the strategy does state an intent to promote people-led service design, including for high-need priority populations. This would be a major reversal to recent trends, where community and Maori primary health care initiatives have struggled to survive, overwhelmed by the mismatch between the growing needs of their communities and the resources made available.

At the technical level, what is required is more effective governance and management within some of the existing instruments.

The capitation formula should encompass more of the fragmented funding streams, and have much stronger pro equity bias. VLCA 7should be enhanced, and universalised to all practices, and used to lower access – effective financial incentives should be available for practices that are providing free care. Currently the capitation formula amounts are based on a person’s age. Health needs are greater for Maori, Pacific and low income people, and the formula should be reflecting this.

Free care for under 6s and free care for under 13s now have cross party political currency and should go further to free care for people with chronic conditions, then free care for the elderly.

The availability of primary care services to the highest needs populations needs to be increased. This will require state investment in infrastructure, provision directly, or through community providers.

Fixing the two system holes – the transfer of government resources meant for the community to the hospitals and the failure to enrol the populations with the high needs into the capitation system should be made the highest priority of the system.

Resisting user pays and privatisation

On a broader level, what is it about our hospitals that have enabled them to effectively resist the countervailing forces of user pays and privatisation? Can we replicate these in the further development of the primary health care system? Can we build a sustainable, powerful sector that is patient-centred, values professional leadership, and resists erosion of its social justice focus? We need to harness the protective effect of a strong professional group or groups within the sector that can shape the primary care institutions and maintain a focus on equity.

The Kurow Cure yet to heal

In conclusion, the Kurow Cure as a vision of health care delivery has stood the test of time. A health system built on the concept of social justice vs charity or flawed market mechanisms is as relevant today as it was in the Waitaki riverbed in the 1930s. It is an embarrassment that 80 years later we still have families living in tents and a politically-led public discourse dehumanising the poor.

I’m confident we as a people, and the people of the health system, can do better.

References:

1. Michael Belgrave, ‘Primary health care – Improving access to health care, 1900s–1970s’, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/primary-health-care/page-3 (accessed 26 November 2016)

2. A medical degree

3. A business degree

4. Independent practitioners association

5. Primary health organisations

6. Analysis of District Health Board Performance to

30 June 2015. The Treasury, New Zealand Government, June 2016

7. Very Low Cost Access

February 23, 2017 at 7:24 am

The story of the three wise men can be seen at the kurow museum and info centre Bledisloe st kurow

LikeLiked by 1 person

March 20, 2017 at 7:34 am

[…] we posted the Kurow Cure, by Professor Don Matheson, last month we thought it may gather a bit of interest. We were quite […]

LikeLike